New to climate change?

Batteries

Batteries are a form of energy storage, which use electrochemical reactions to create a flow of electricity. Once used mainly for portable electronics, batteries are becoming larger, cheaper, and more versatile, allowing them to play a growing role in our energy system.

New types of batteries help us take full advantage of cheap solar and wind energy. With batteries, we can store energy when there’s plenty of sun and wind, and use it later when the weather is less favorable. Batteries can also protect us from storms, heatwaves, and other events that damage the power grid: With batteries, local communities and critical facilities like hospitals can run on stored energy in an emergency. And by supporting electric vehicles and clean solar and wind power, batteries help us travel and meet our energy needs with far less climate-warming pollution.

What makes a battery

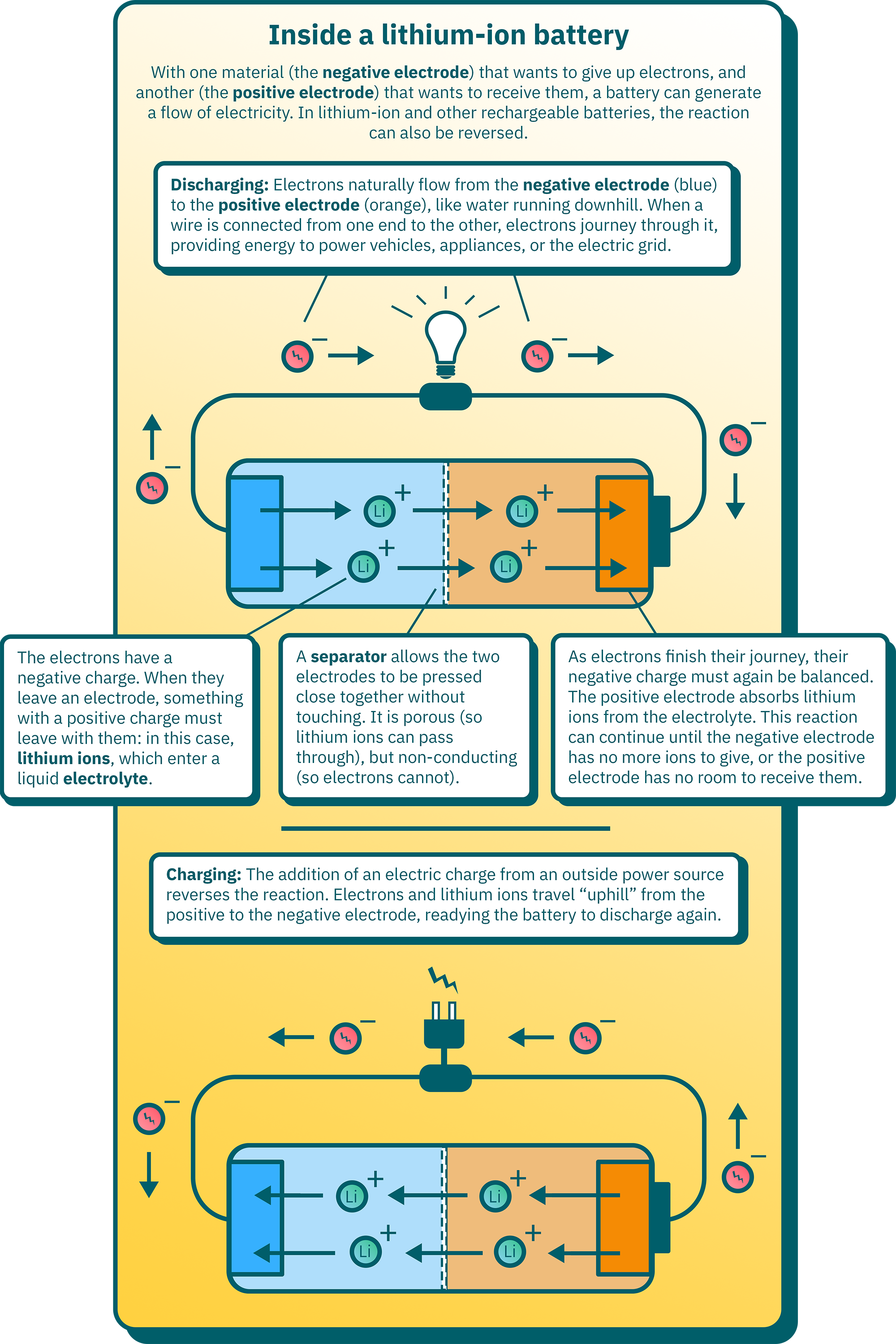

Batteries work through the movement of electrons from one material to another. At one end of the battery is a “negative electrode” in which electrons are stored in a high-energy state. You can think of these electrons like water behind a dam: Open a gate for them, and they will naturally flow and release their energy.

At the other end of the battery is a “positive electrode” to receive the electrons in a lower-energy state.1 When the battery is discharging, a wire connects the two ends, and electrons travel through the wire, like water flowing downhill. This flow of electricity passes through devices we want to power, like the motor of an electric car.

Because the electrons carry a negative charge, this reaction must be balanced by positively-charged ions moving in the same direction. To accomplish this, the battery contains an “electrolyte” between its two electrodes, usually a liquid solution in which ions with different charges move freely. As the battery discharges, the negative electrode dumps positively-charged ions into this electrolyte broth, and the positive electrode accepts them.

In this way, electrons and ions move from one side of the battery to the other, until one electrode is depleted and the other is full.

In rechargeable batteries, a supply of electricity can also move both ions and electrons back to where they began, like water being pumped uphill.

Because many materials can serve as negative electrodes, positive electrodes, and electrolytes, batteries can be made for many different needs. Battery engineers must balance the cost, durability, and safety of different designs. They also consider properties like “energy density” (how much energy a battery can store for its size and weight), and how quickly it can charge and discharge. All these features are important, but which are most important depends on how the battery will be used.

Lithium-ion batteries and electric transportation

Lithium is the lightest metallic element in the universe. This feature is the basis of “lithium-ion” batteries, a technology that stores plenty of energy in a small package, perfect for handheld electronics like cellphones.

It’s also ideal for electric vehicles (EVs). Cars and trucks need to hold a lot of energy to travel long distances, and can’t be too heavy. Since 2010, rapid advances in lithium-ion technology have brought battery costs down 90%,2 giving us electric cars that can travel hundreds of miles on a single charge while competing with gasoline-powered cars on price.3

EV battery design is still evolving. Most lithium-ion batteries contain flammable electrolytes, leading to rare but dangerous EV fires. To prevent this, researchers are working on “solid state” batteries in which ions move through solid materials.

This innovation might also enable “lithium metal” batteries, in which the lithium exists as a pure metal, rather than being stored in a host material.4 Unfortunately, today’s early lithium metal batteries degrade too quickly for most practical uses. If this can be solved, they will offer even higher energy density than the lightest batteries today, powering heavier vehicles or extending the range of lighter ones.

Sodium, another lightweight metal, might also fill a useful niche. Some researchers believe sodium-ion batteries could be made at lower cost than lithium-ion, for cheaper cars built to go shorter distances—or perhaps for use on the electric grid.

New chemistries and grid-scale storage

Decades of work on small electronics and vehicles have made lithium-ion batteries so cheap, dependable, and long-lasting that they can also be cost-effectively used on the electric grid. Large battery farms are now helping us get more of our energy from solar and wind, without compromising reliability.

But here, it’s not obvious that lithium is the future. The advantage of lithium, its light weight and portability, is not so important in a battery farm that’s not going anywhere.

Today, most battery farms are used for short-term energy storage, typically supplying electricity for eight hours or less. In a grid with a growing share of wind and solar power, that’s a useful service. Battery farms can smooth out a wind or solar farm’s output as the weather changes throughout the day. They can keep energy from being wasted in places like California, which produce more solar energy in the middle of a sunny day than the grid needs. They can also perform “peak shaving,” offering some extra energy in the early evening as people come home from work and energy use spikes. This helps utilities get through this 1- to 4-hour peak without the cost and strain of quickly firing up fossil fuel plants.

Lithium-ion batteries are great for short-term storage because they can charge and discharge quickly. But with even heavier reliance on solar and wind, the grid will also need overnight storage, storage for windless days, and some reserve storage for winter when there’s less sun. For these uses, the grid would benefit from the cheapest battery chemistries we can invent, to keep driving down the price of clean energy.

One chemistry that stands out is “iron-air.” The negative electrode is cheap, abundant iron, and the positive electrode is the oxygen in the air itself. Massive, heavy, and slow to charge and discharge, iron-air batteries are poorly suited to the main markets for batteries today, but may hold promise for long-duration, grid-scale storage.

Another emerging technology is the redox flow battery. These batteries store their charge, not in solid electrodes, but in two tanks of liquid electrolytes: one positive and one negative. To charge or discharge the battery, the liquids are pumped into a reactor where electrons and ions can flow between them. While this design is bulkier than other batteries, it also lasts a long time, is compatible with cheap materials, and is easy to grow, shrink, or reconfigure for different uses.

Published October 31, 2025.

1 The negative and positive electrode are often called the “anode” and “cathode,” respectively. This is, however, not always accurate, or is at least a little confusing. By definition, an anode is a material that undergoes “oxidation” and gives up electrons, while a cathode is a material that undergoes “reduction” and gains electrons. Therefore, when a battery is discharging, the negative electrode is an anode and the positive electrode is a cathode. But during recharging, electrons move the other way, and the two flip. For rechargeable batteries, then, it’s simpler to think of the materials in terms of their electric potential: a positive electrode, which always has a higher potential, and a negative electrode, which always has a lower one.

2 International Energy Agency: "Batteries and Secure Energy Transitions," within World Energy Outlook 2023, April 25, 2024.

3 International Energy Agency: Global EV Outlook 2025, May 14, 2025.

4 In a lithium metal battery, this pure lithium would form the negative electrode. This is a notable difference from today’s lithium-ion batteries, in which the negative electrode is typically a porous structure of graphite and/or silicon that hosts lithium ions during charging. Those ions originate from the positive electrode, where they are bound within a compound of other elements in which lithium can be removed and reinserted without structural degradation (for example, lithium cobalt oxide or lithium iron phosphate).