In the middle of the night in September 2005, Warren Madden ’85 sat onboard a WC-130J aircraft that was being tossed about by ferocious wind and driving rain. “It was a pretty bumpy ride,” Madden acknowledges gleefully. At last, the plane punched through the eyewall of Hurricane Rita. (More on what Madden was doing inside that hurricane in a moment.)

In most Category 5 hurricanes, the eye is bowl-shaped. “We call it the stadium effect,” says Madden, and that’s because the 10-mile-high thunderstorms slope upward at the angle of stadium seating. But Rita was different. It was so intense and strengthening so quickly that the eyewall was nearly vertical, “like a stovepipe” with a 20-mile diameter. Above the plane, there wasn’t a cloud in the sky—just a full moon shining down over the lip of the raging storm. And ahead was lightning, crackling across the face of the eyewall. “It was enormously beautiful,” Madden whispers with a reverence born from the acute understanding that a hurricane of Rita’s power could easily rip apart an aircraft and everyone onboard. A couple days later, the storm slammed into the Texas-Louisiana border, bringing high winds, storm surge, flooding, and fatalities.

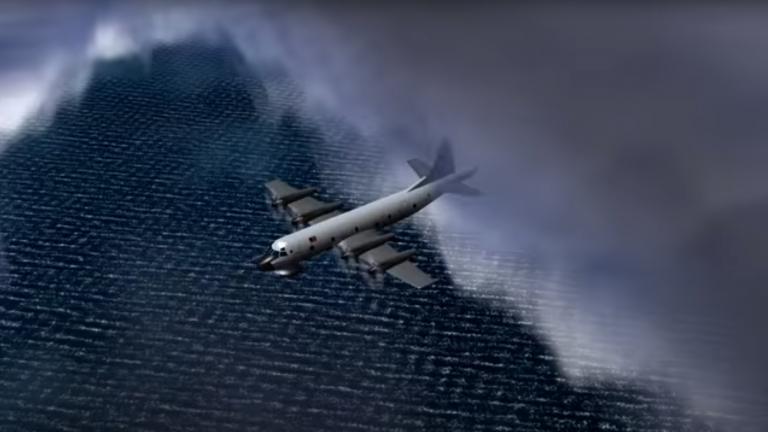

Between 1998 and 2012, Madden worked as a Hurricane Hunter—a member of the US Air Force Reserve’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, which flies into “everything from little tropical depressions to monster Cat 5s.” Radar and satellite imagery is akin to taking an X-ray of a storm, he explains, But to get a more detailed “atmospheric biopsy” involving information like a hurricane’s maximum wind speed, its central pressure, and the exact location of its eye (since clouds can obscure satellite observations), you have to fly into the belly of the barometric beast and sample it from within. Those data inform computer models, helping to narrow the possible paths of a hurricane, predict storm surge, and improve the accuracy of forecasts by up to 25 percent.

These days, Madden leads the air force’s Chief, Aerial Reconnaissance Coordination, All Hurricanes (CARCAH) unit at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Hurricane Center in Miami, Florida. He helps determine what information the forecasters at the National Weather Service need the Hurricane Hunters to gather, then helps schedule flights accordingly. During peak hurricane season, when the demand for data is high and the availability of planes and personnel is stretched thin, Madden says it’s like “playing five-dimensional aircraft chess.”

Madden, who grew up in the Boston area, became fascinated with weather at the age of five, when he read an article in the newspaper about a tornado outbreak in Texas that obliterated entire houses. “I didn’t realize wind could do that,” he recalls. He became convinced he would study meteorology. But in the 10th grade, he fell in love with computers, and he glided into a major in computer science at MIT on an ROTC military scholarship. He was also actively involved as a performer with the MIT Musical Theatre Guild. After leaving the Institute and wrapping up a few years of active duty in the air force, that theatrical background “set me up for an opportunity to get into television,” first as a local meteorologist in Dayton, Ohio, and then as a national figure on the Weather Channel.

Today, much of the information about hurricanes seen on the Weather Channel, lighting up the green screen behind the meteorologist, has made its way through Madden’s office at CARCAH. When the storms get really active in the late summer and early fall, he and two coworkers each take an eight-hour shift, collectively working around the clock until Mother Nature quiets down.

Madden is often asked why in this modern era we’re still willing to send men and women into the vertiginous fury of a hurricane. “We put our lives on the line,” he answers matter-of-factly, “to help protect everyone else’s lives.” The wet and windy numbers collected from the heart of a storm directly inform the evacuation orders of emergency managers, and it’s those orders that save people. “That,” says Madden, “is why we still do this.”