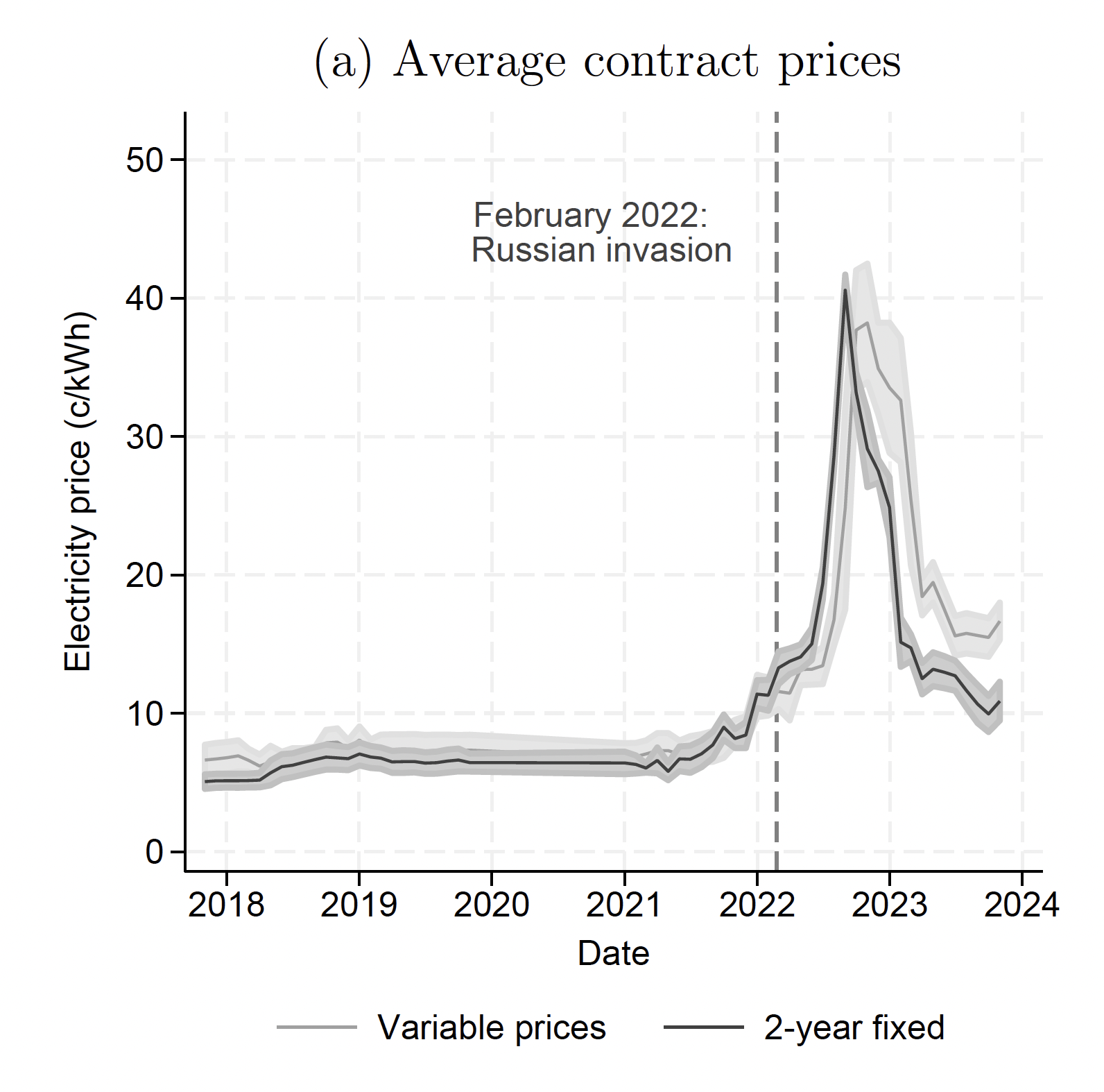

Figure 1. Mean electricity contract prices in Finland.

High energy prices—driven by supply disruptions, renewable energy intermittency, and climate policies—have become central to policy discussions. A key concern is the financial burden that high energy prices impose on households. Assessing whether this concern is justified requires understanding households’ capacity to adjust to elevated energy costs. The European Energy Crisis created a natural experiment to study how households respond when energy prices rise unexpectedly.

To identify causal effects of high energy prices, we exploit a natural experiment based on the quasi-random expiration dates of two-year, fixed-price electricity contracts. Households whose contracts expire during the peak of the crisis suddenly faced large, overnight price increases (the “treated” group), while those with contracts ending later still paid their lower, pre-crisis rates (the “control” group). Using a stacked difference-in-differences research design, the study identifies significant differences in households’ ability to respond. When energy prices double, the households respond as follows:

Electricity Use: Households reduce their electricity consumption by about 18.4% in response to a doubling of the electricity price. Higher-income households are more responsive, likely because they can afford efficiency upgrades or have more discretionary usage to cut back.

Labor Earnings: Households overall increase labor earnings by about 1.4% in response to doubling electricity costs. This effect is strongest among middle-income groups. Low-income households often have weaker labor-market attachments, limiting their ability to earn more.

Financial Distress: We find about a 0.4 percentage-point rise in default probability (roughly a 4% overall increase) follows a price doubling. Low-income and heavily indebted households are at the highest risk, while high-income households avoid serious financial distress.

Residual Consumption: Using the administrative data, we can impute households’ residual consumption and savings. On average, we find that households reduce residual consumption by 4.5%. Low-income lack other adjustment channels and must cut back spending more, amplifying inequality.

Beyond the direct effects, our setting allows us to study anticipation effects. By observing behavior in the months leading up to contract expiration, we find that households are forward-looking and reduce electricity consumption several months before their contracts expire. We do not find similar effects for households whose electricity retailer abruptly goes bankrupt during the crisis. Also, similar anticipation effects are not observed for earnings. A longer anticipation period alleviates some negative effects of the energy price increase, but does not completely remove them.

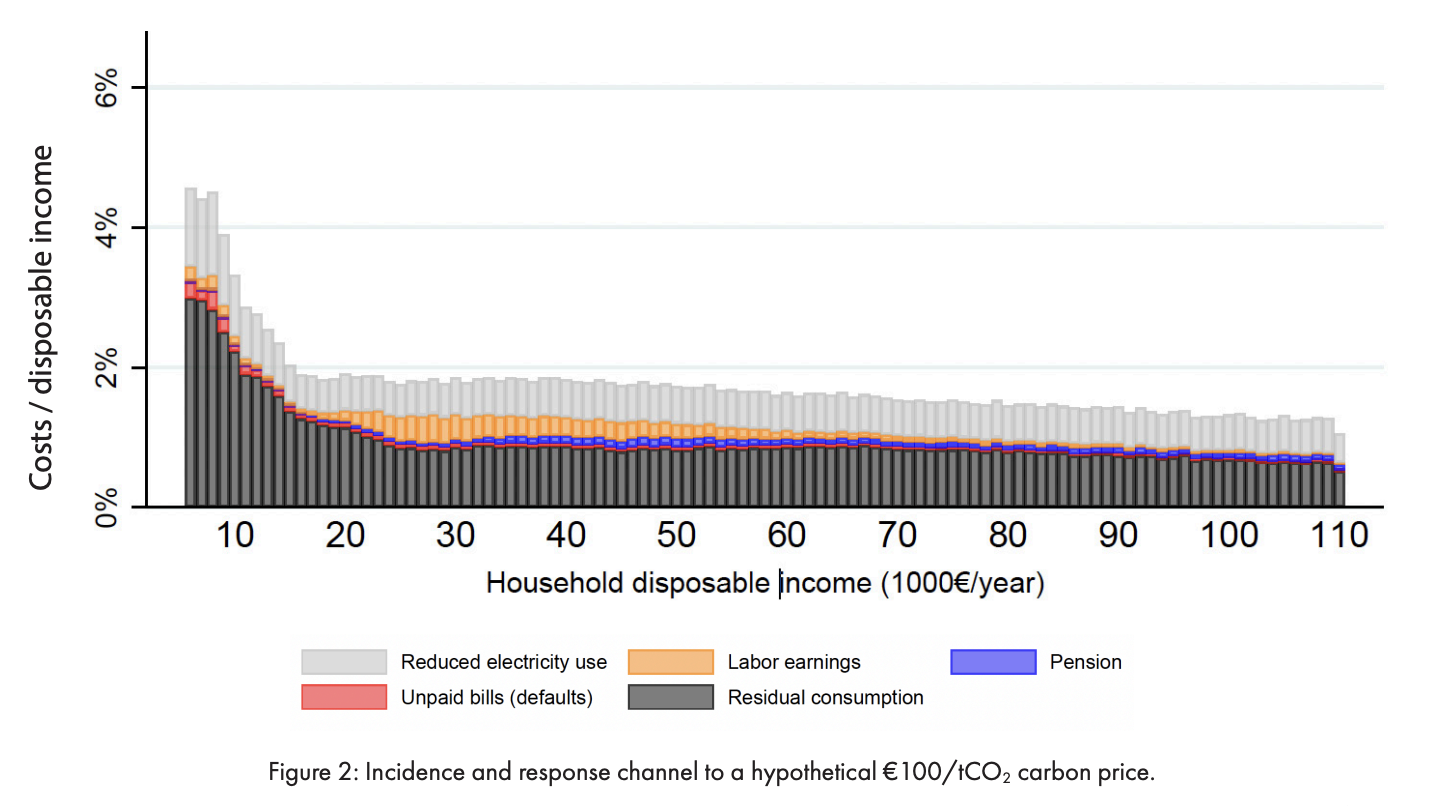

Beyond the energy crisis, the estimated household-level responses teach us about impacts of other policies that influence energy prices, such as climate policies. We use the estimated behavioral effects to simulate household-level responses to a hypothetical €100/tCO2 carbon price; shown in Figure 2. Our results identify three channels through which low-income households are affected by carbon pricing: (i) they spend a larger share of disposable income on electricity, (ii) they have lower demand elasticity, and (iii) they are less able to increase earnings. These response channels help medium- and high-income households to reduce their cost burden by around one half, but low-income households only by less than one fourth. As a result, the low-income households face a higher risk of default, and they are forced to reduce their already low residual consumption further.