With a novel communications infrastructure, the Civic Design Initiative aims to support communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis.

The climate crisis is a novel and developing chapter in human and planetary history. As a species, humankind is still very much learning how to face this crisis, and the world’s frontline communities — those being most affected by climate change — are struggling to make their voices heard. How can communities imperiled by climate change convey the urgency of their situation to countries and organizations with the means to make a difference? And how can governments and other powerful groups provide resources to these vulnerable frontline communities?

The MIT Civic Design Initiative (CDI), an interdisciplinary confluence of media studies and design expertise, emerged in 2020 to tackle just these kinds of questions. It brings together the MIT Design Lab, a program originally founded in the School of Architecture and Planning with its research practices in design, and the Comparative Media Studies program (CMS/W) with its focus on the fundamentals of human connection and communication. Drawing on these complementary sources of scholarly perspective and expertise, CDI is a suitably broad umbrella for the range of climate-related issues that humanistic research and design can potentially address.

Based in the Comparative Media Studies program (CMS/W) of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, the initiative is responding to the climate crises with a spirit of inquiry, listening, and solid data. Reflecting on the mission, James Paradis, Robert M. Metcalfe Professor of CMS/W and CDI faculty director says the core idea is to address global issues by combining new and emerging technologies with an equally keen focus on the social and cultural contexts — the human dimensions of the issue — with many of their nuances.

Working closely with Paradis on this vision are the two CDI co-directors: Yihyun Lim, an architect, urban designer, and MIT researcher; and Eric Gordon, a visiting professor of civic media in MIT CMS/W. Prior to CDI, when she was leading the MIT Design Lab research group, Lim says “At MIT Design Lab, I was working within the realm of applied research with industry partnerships, how we can apply user-centered design methods in creating connected experiences. Eric, Jim, and I wanted to shift the focus into a more civic realm, where we could bring all our collective expertise together to address tricky problems.

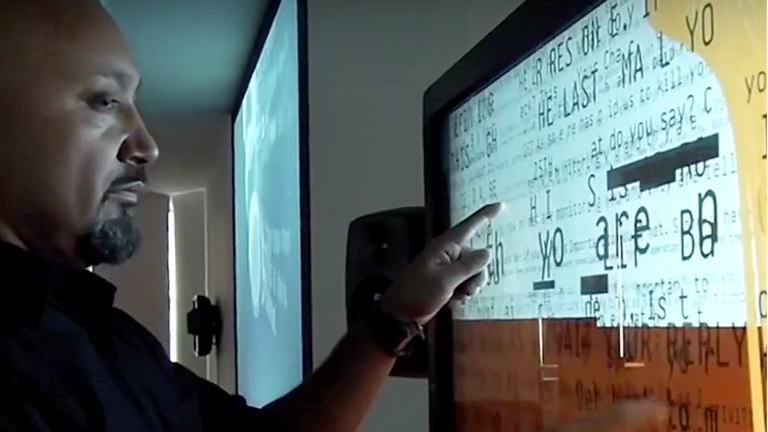

Watch Video: Activating Climate Imaginaries

Deep Listening

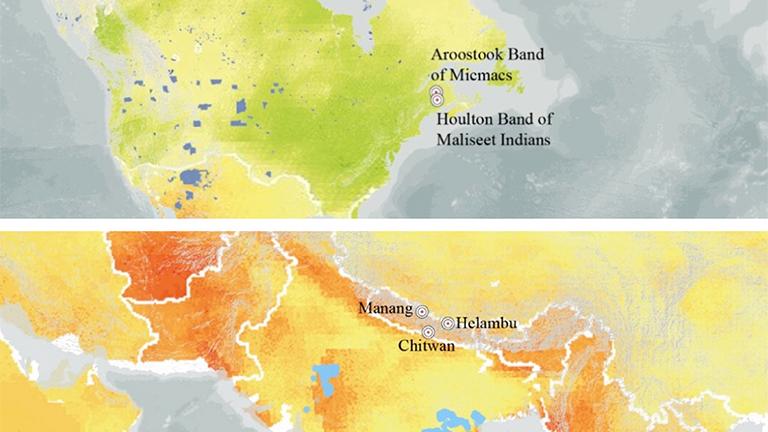

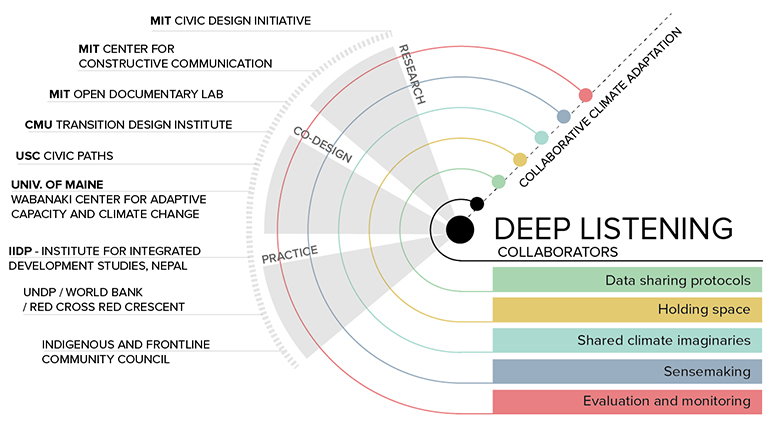

The Initiative’s flagship project, the Deep Listening Project, is currently working with a small initial group of frontline communities in Nepal and indigenous tribes in the U.S. and Canada. The work is a direct application of communication protocols: understanding how people are communicating with and often without technologies — and how technologies can be better used to help people get the help they need, when they need it, in the face of the climate crisis.

The CDI team describes deep listening as "a form of institutional and community intake that considers diversity, tensions and frictions, and that incorporates communities’ values in creating solutions.

Globally, the majority of climate response funding currently goes toward mitigation efforts — such as reducing emissions or using more eco-friendly materials. It is only in recent years that more substantial funding has been focused on climate adaptation: making adjustments that can help a community adapt to present changes and impacts and also prepare for future climate-related crises. For the millions of people in frontline communities, such adaptation can be crucial to protecting and sustaining their communities.

Gordon describes the scope of the situation: “We know that over the next ten years, climate change will drive over 100 million people to adapt where and how they live, regardless of the success of mitigation efforts. And for those adaptations to succeed, there must be a concerted collaborative effort between frontline communities and institutions with the resources to facilitate adaptation. Communication between institutions and their constituents is a fundamental planning problem in any context,” Gordon continues. “In the case of climate adaptation, there will not be a surplus of time to get things right. Putting communication mechanisms in place to connect affected communities with institutional resources is already imperative.

“This situation requires that we figure out, quickly, how to listen to the people who will rely on [those institutions] for their lives and livelihoods. We want to understand how institutions — from governments to universities to NGOs — are adopting and adapting technologies, and how that is benefiting or hurting their constituencies. People with direct frontline experience need to be supported in their speech and ideas, and institutions need to be able to take in the data from these communities, listen carefully to discern its significance, and then act upon it.”

Sensemaking: Infrastructure for connection

One important aspect of meaningful, effective communication will be the ability of frontline and indigenous communities to communicate likely or imagined futures, based on their own knowledge and desires. One potential tool is what the Initiative calls “sensemaking”: producing and sharing data visualizations that can communicate to governments the experiences of frontline communities. The Initiative also hopes to develop additional elements of the “deep listening infrastructure” — mechanisms to make sure important community voices carry and that important data isn’t lost to noise in the vast question of climate adaptability.

“Oftentimes in academia, the paper gets published or the website gets developed, and everybody says, ‘Okay, we’ve done our work,’” Paradis observes. “What we’re aiming to do in the CDI is the necessary work that happens after the publication of research — where research is applied to actually improve peoples’ lives.”

The Deep Listening Project is also building a network of scholars and practitioners nationwide, including Henry Jenkins, co-founder and former faculty member at MIT CMS/W, and Sangita Shresthova, CMS SM’03, at the University of Southern California and Darren Ranco at the University of Maine. Ranco, an anthropologist, Indigenous activist, and organizational leader, has been instrumental in connecting with Indigenous groups and tribal governments across North America.

Meanwhile, Gordon has helped forge connections with groups like the International Red Cross/Red Crescent, the World Bank, and the UN Development. At the root of these connections is the impetus to communicate lived realities from the level of a small community to that of global relief organizations and governmental powers.

Both large institutions and individual communities imagine, separately — and hopefully soon together — how the human world will reshape itself to be viable in profoundly shifting climate conditions.

Potential human futures

Mona Vijaykumar, a second-year student in the SMArchS Architecture and Urbanism program in the Department of Architecture, and among the first student researcher assistants attached to the new Initiative, is excited to have the chance to help build CDI from the ground up. “It’s been a great honor to be working with CDI's amazing team for the last 8 months,” she says.

With her background in urban design and research interest in climate adaptation processes, Vijaykumar has been engaged in developing the Deep Listening Project’s white paper as part of MIT Climate Grand Challenge. She works alongside the Initiative’s two other inaugural research assistants: Tomas Guarna, a master’s student in CMS, and Gabriela Degetau, a master’s student in the SMarchS Urbanism program with Vijaykumar.

“I was involved in analyzing the literature case study on community based adaptation processes and co-writing the white paper,” Vijaykumar says, “and am currently working on conducting interviews with communities and institutions in India. Going forward, Gabriela and I will be presenting the white paper at gatherings such as the American Association of Geographers’ Conference in New York and the Climate and Social Impact Conference in Vancouver.”

“The support and collaboration of the team have been incredibly empowering,” reflects Degetau, who will be co-presenting the white paper with Vijaykumar in New York and Vancouver. “Even when working from different countries and through Zoom, the experience has been unique and cohesive.”

Both Degetau and Vijaykumar were selected as the first fellows of the Vuslat Foundation, organized by the MIT Transmedia Storytelling Initiative. In this one-year fellowship, they are seeking to co-design “climate imaginaries” through the Deep Listening Project. Vijaykumar’s work is also supported by the MIT Human Rights and Technology Fellowship for ‘21-’22, which guides her personal focus on what she refers to as the “dual sword” of technology and data colonialism in India.

As the Deep Listening Project continues to develop a sustainable and balanced communication infrastructure, Lim reflects that a vital part of that is sharing how potential futures are envisioned. Both large institutions and individual communities imagine, separately — and hopefully soon together — how the human world will reshape itself to be viable in profoundly shifting climate conditions.

“What are the possible futures?” asks Lim. “What are people dreaming?”

Suggested links

Civic Design Initiative Website

MIT Comparative Media Studies/Writing

James Paradis, Robert M. Metcalfe Professor of Comparative Media Studies/Writing

Story prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Editorial and Design Director: Emily Hiestand

Senior Communications Associate: Alison Lanier

Published 15 December 2021