We evaluated the system cost of providing electricity and heat to serve the load profiles of two types of Alaskan communities, and calculated the cost efficiency of including a nuclear microreactor in the generation portfolio. We employed a capacity expansion and dispatch model augmented to co-optimize heat and electricity generation. Since microreactor designs are still in development and the eventual capital costs are speculative, our strategy was to explore the outcomes across a wide range of capital costs, and find the range in which a microreactor is included in the least-cost portfolio and the range in which it is not. We call the boundary between the two the capital cost ceiling.

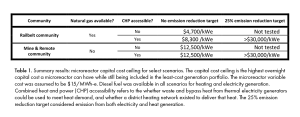

We have identified the microreactor capital cost ceiling under a range of assumptions and scenarios. This includes two different load profiles—one reflective of demand across Alaska’s Railbelt communities, and one reflective of demand at a remote Alaskan mine and neighbouring community. We assessed the impact of natural gas fuel availability, whether a community had a district heating network, future reductions in the capital cost of renewables, the price of fossil fuels, and, last-but-not-least, the need to reduce systemwide emissions.

Three factors appear to play a dominant role in setting the capital cost ceiling and answering whether a microreactor is likely to be a cost-efficient addition to the system. One of these is the availability of natural gas. Natural gas is a much cheaper source of energy than diesel fuel, and therefore the microreactor capital cost ceiling is significantly lower in communities where it is available. Most communities in the Alaskan Railbelt have access to natural gas, while few, if any, of the other communities do.

The second factor is the size of the heat load and the accessibility of a district heating network. In our results, the capital cost ceiling was much higher in scenarios where a microreactor’s waste heat was highly utilized. Communities in the Alaskan Railbelt have higher heat loads and select ones have accessible district heating networks, which facilitated the use of microreactor waste heat, and set the capital cost ceiling high. In contrast, a remote community anchored by a mine has a relatively smaller heat load, which would set the capital cost ceiling lower.

The third, and overwhelmingly most important factor, is the goal of emission reductions. Any modest emissions reduction target dramatically raised the capital cost ceiling for a microreactor, reflecting that the microreactor is very cost-efficient among low carbon options when heat and electricity are considered together. This conclusion holds broadly across both load profiles. We focused on CO2 emissions. However, we are aware that certain Railbelt communities face a critical need to reduce particulates and other criteria pollutants. Recognizing this would further boost the competitiveness of a microreactor.

References

J. Buongiorno, B. Carmichael, B. Dunkin, J. Parsons and D. Smit, “Can Nuclear Batteries Be Economically Competitive in Large Markets?,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 14, 2021.

D. Shropshire, G. Black and K. Araujo, “Global Market Analysis of Microreactors,” INL/EXT-21-63214, 2021.

G. Holdmann, G. Roe, S. Colt, H. Merkel and K. Mayo, “Small Scale Nuclear Power: an option for Alaska, January 2021 Update,” Univ. of Alaska Fairbanks, 2021.

J. Jenkins and N. Sepulveda, “Enhanced decision support for a changing electricity landscape: The GenX configurable electricity resource capacity expansion model,” MITEI, 2017.

Further Reading: CEEPR WP 2021-018

About The Authors

|

Dr. Ruaridh Macdonald is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering at MIT. His research focuses on understanding how nuclear power systems must change in order to succeed in modern energy systems and markets, and developing new designs in response. Ruaridh completed his undergraduate degree and Ph.D in Nuclear Science and Engineering at MIT. |

|

John E. Parsons is a Senior Lecturer in MIT’s Sloan School of Management, an Associate Director of CEEPR and a co-Chair of the MIT study on The Future of Nuclear Energy in a Carbon-Constrained World. |